Diversified vineyards support bird communities – new research by a SUFICA investigator

Blog written by Natalia Zielonka and reviewed by Andrés Muñoz‐Sáez

Wine grape agriculture is globally important but comes at potential costs to biodiversity as native habitats are lost to production. Conservationists worldwide are after win-win solutions for agricultural production and conservation, making research within agroecosystems key. Here, Andrés Muñoz‐Sáez, who is a SUFICA project co-investigator, shows the value of native vegetation fragments within and adjacent to vineyards in enhancing bird communities.

Link paper: Muñoz‐Sáez, A., Kitzes, J. and Merenlender, A.M. (2020) Bird friendly wine country through diversified vineyards. Conservation Biology. Accepted Author Manuscript. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13567

Vineyards in Chile – why are they important?

Wine grapes are one of the most globally important crops, covering approximately 7.5 million hectares worldwide. The wine grape industry is a key contributor to the economy sector of many countries, where it also has an important role in poverty reduction. However, just like other types of agriculture, vineyards pose threats to biodiversity by contributing to land-use changes, habitat loss and fragmentation. It is thus important to investigate the relationships between bird communities and wine grape agriculture to inform practices that make wine production and bird conservation compatible.

Four areas within the Mediterranean Basin – California, Chile, South Africa and Australia – are global biodiversity hotspots and are known for their high degree of endemism. They are also known for their wine grape production, but this has been linked to habitat loss and viniculture is a named threat to biodiversity within these hotspots. Limited evidence is available on the value of native vegetation within and surrounding vineyards, which hinders the development of management approaches that would benefit both the production and conservation.

How was the study performed?

Andrés and colleagues studied the effects of native vegetation on bird communities within and around Chilean vineyards.

The study took place in central Chile, which is characterised by Mediterranean climate and the native vegetation is dominated by sclerophyllous forest and matorral (see image above). This area is also important for wine grape production, representing almost 37% of the national vineyard land cover.

Bird communities were surveyed by point counts across 20 vineyards and surrounding landscapes (total of 120 survey points). Survey points were evenly distributed across (1) vineyards with no remnant vegetation, (2) vineyards with remnant vegetation, and (3) remnant vegetation adjacent to vineyards. Surveys were performed in 2014 and 2015 during spring-summer (October-January), so they overlapped with the birds’ breeding season.

What was found?

In total, Andrés recorded over 5000 individual birds belonging to 48 species. Species richness was positively influenced by native vegetation and the total bird detections were significantly lower in vineyards.

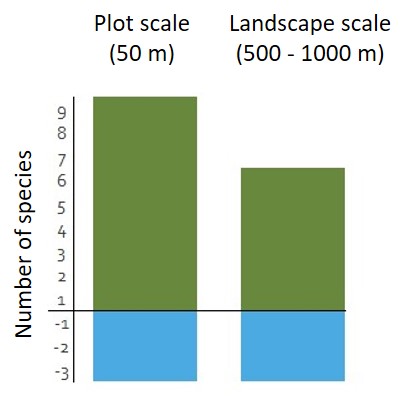

Out of the recorded species, 30 were present in >5 survey locations which allowed species’ presence to be related to habitat types. The results are summarised below (Figure 1), and it is clear that more species (15 vs. 6) showed positive relationships with native vegetation cover.

Andrés and colleagues were also able to split bird species by feeding guilds to further disentangle recorded patterns in bird communities. They found that:

- Bird communities were significantly different between native vegetation patches and vineyards for all feeding guilds but omnivores

- Insectivorous species were positively associated with native vegetation cover

- Granivorous species were more frequently detected in native vegetation remnants than in vineyards

Importantly for conservation of rare species, the study further confirmed the importance of native vegetation for endemic species, whose presence was positively related to native vegetation cover.

What does this mean for conservation?

This study is an important contribution to the field of agroecology, showing the importance of retaining native vegetation fragments within vineyards to help conserve bird species. Without these remnants, many endemic, insectivorous and granivorous species would disappear from these landscapes, leaving a much more uniform community behind.

Losing bird species from agricultural landscapes, such as vineyards, does not only compromise the species’ conservation, decreases aesthetic value of the landscape but could also have negative consequences for wine grape production. Insectivorous bird species, such as the House Wren Troglodytes aedon, Tit-Spinetail Leptasthenura aegithaloides or Tufted Tit-tyrant Anairetes parulus, were present within vineyards with remnants of native vegetation and they may provide an ecosystem service in the form of biological pest control, helping to control pest outbreaks within grapes and positively impact grape production.

Worryingly, a common and a frequently observed trend is the negative impact of agricultural land on endemic species. In this system, two-thirds of endemic species were more frequently recorded within native vegetation than within vineyards. This could be due to the species’ characteristics as here, many endemics (e.g. Dusky-tailed Canastero Pseudasthenes humicola, Dusky Tapaculo Scytalopus fuscus) had low dispersal potential due to low relative mobility, meaning that they are more restricted to native vegetation patches. Such species are likely to disappear with disappearing native vegetation, further highlighting the importance for protecting remnant vegetation within vineyards, and large patches surrounding agricultural landscapes.

Link to SUFICA

At SUFICA, we are carrying out similar research within Brazilian fruit production systems and Andrés performed the baseline bird monitoring within with SUFICA farms. Our aims are to study bird communities across grape, mango farms and the native habitat of Caatinga to better understand how intensive fruit production affects bird communities. Secondly, we aim to understand the impact of bird species on grape production, namely their contributions to biological pest control and damage to grapes. This work is being carried out with the aim to inform evidence-based management practices that benefit both the production and biodiversity conservation.

To keep up to date with studies published by the members of the SUFICA team, head over to the Publications section of the website and follow us on Twitter @SUFICA_Caatinga.

Natalia Zielonka

24.06.20